“In leadership we see morality magnified, and that is why the study of ethics is fundamental to our understanding of leadership.” ~ Dr. Joanne Ciulla

The COVID-19 global pandemic, ongoing racism, high-profile scandals, and much more, have made the need for improved ethics education, for both current and future leaders, abundantly clear. Leadership theory and research strongly supports the importance of ethics, as indicated below. Leadership theory often mentions “positive change”, but what is “positive change”? What counts as “positive change” is too often assumed, however when we look at the national news “positive change” is often hotly debated (e.g. immigration). Ethics, or moral philosophy, is a field that has been focused on this question for thousands of years and has a lot to teach us about positive change and leadership. However, there is also new cutting-edge research in the field of Behavioral Ethics which infuses a lot of research from psychology and sociology, and can inform and inspire our work.

How are ethics and leadership linked? (Leadership Theory and Research)

- Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS): “… many colleges refocused efforts on leadership development when events such as the Watergate scandal caused institutions to ponder how they taught ethics, leadership, and social responsibility.” (CAS, 2012)

- MasonLeads, core leadership assumption #8: “Leadership is ethical and is values-driven: Leadership includes ethical action, both in the process and outcomes. The consistent demonstration of honest and ethical decision-making and behavior by leaders form the foundation of trust and credibility on which relationships are built and maintained.”

- International Leadership Association (ILA) Guidelines for Leadership Education Programs: “Critical to the development of leadership programs is the question of ethics and how the program addresses questions of ethics.” (ILA Guiding Questions)

- Relational Leadership Model (RLM), Leadership Definition: “A relational and ethical process of people together attempting to accomplish positive change.”

- The Social Change Model of Leadership (SCM) is the most commonly used model at colleges and universities in the US. The SCM focuses on leadership values and positive social change, both aspects of ethics. Ethics can help us clarify what is positive social change (e.g. access for people with disabilities) as opposed to negative change (e.g. increased activity of white supremacists). The values of the Social Change Model are linked with ethics (e.g. Congruence, Citizenship).

- National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE): “Developing a Personal Code of Values and Ethics” is listed as an important area of learning and development.

- Illinois Leadership Center, Benchmarking Report: “The future focus of leadership programs is targeted toward expanding leadership education into new domains such as global leadership, social entrepreneurship, ethics, and sustainability.” (Illinois Leadership Center, 2013)

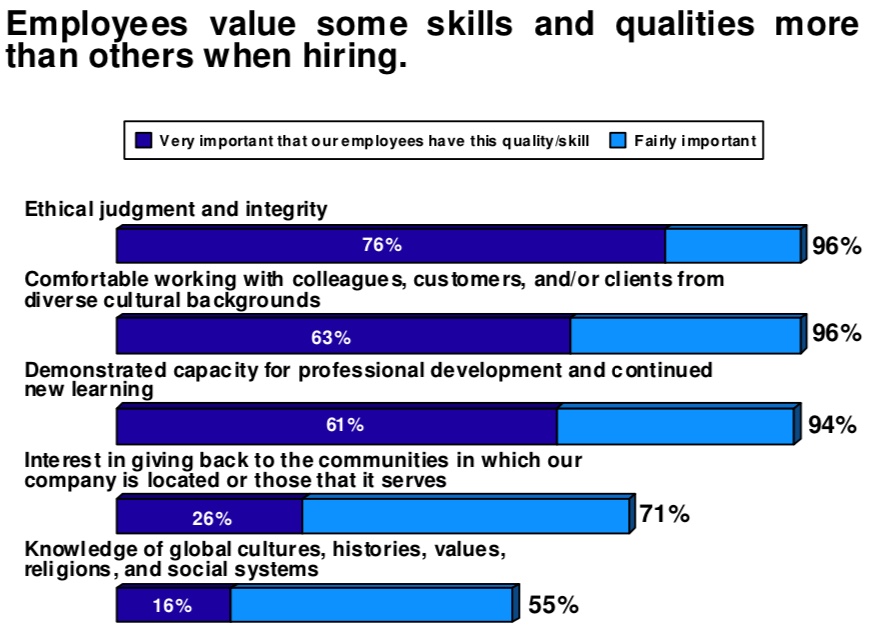

- Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U): “Employers point to a variety of types of knowledge and skills as important considerations when hiring, placing the greatest priority on ethics…”

- When asked how important it was that their employees “Demonstrate ethical judgment and integrity”, 96% of employers rated it as important (including 76% rating it as “very important”). (AAC&U, 2013)

What is ethics? (Ethics Theory: Misconceptions and Reality)

- Ethics is NOT just rules, laws, policies or a focus on compliance or “ethics violations.” Ethics is a discussion of how we should live and lead based on principles of moral philosophy that have been refined over more than 2,000 years. For a humorous take on how ethics is misinterpreted, see the TV show The Office, Ethics Day episode…

- Holly: “… Say my name is Lauren and here I am shopping in a supermarket and I steal a pencil. That’s not right.”

- Michael: [coughs to hide his words] “Lauren, [coughs] enough with the pencils.”

- Holly: “No, I have to go over pencils and office supplies. It’s part of the ethics thing.”

- Oscar: “That isn’t ethics. Ethics is a real discussion of the competing conceptions of the good. This is just the corporate anti-shoplifting rules.”

- The Markkula Center for Applied Ethics has summarized some major misconceptions about ethics: “… sociologist Raymond Baumhart asked business people, ‘What does ethics mean to you?’ Among their replies were the following”:

- “Ethics has to do with what my feelings tell me is right or wrong.”

- “Ethics has to do with my religious beliefs.”

- “Being ethical is doing what the law requires.”

- “Ethics consists of the standards of behavior our society accepts.”

- “I don’t know what the word means.”

- None of the answers above is fully correct, except for maybe the last one, depending on the person. In reality, ethics refers to well-founded standards of right and wrong and addresses the question “how should we live and lead?” (See https://www.scu.edu/ethics/ethics-resources/ethical-decision-making/what-is-ethics/)

What are the high-impact practices? (Ethics Research)

- Ethical Decision-Making

- AAC&U has created an Ethics Reasoning VALUE Rubric. It was developed by a team of faculty experts representing colleges and universities across the United States.

- LEAD uses this rubric in designing their ethical decision-making initiatives in addition to other rubrics that we created as part of the development of the Patriot Experience (AAC&U, 2009).

- AAC&U has created an Ethics Reasoning VALUE Rubric. It was developed by a team of faculty experts representing colleges and universities across the United States.

- Behavioral Ethics

- “There is significant evidence… that teaching behavioral ethics is a promising new approach for improving the ethicality of students’ decisions and actions.” (Prentice, 2015)

- “Ethics Unwrapped” from the University of Texas at Austin has a FREE ethics video series that focuses on behavioral ethics as it applies to leadership and beyond.

- United Nations Global Goals (https://www.globalgoals.org/)

- In September 2015, world leaders from all 193 member states of the UN agreed to 17 goals for a better world by 2030. “These goals have the power to end poverty, fight inequality and stop climate change.” (https://www.globalgoals.org/)

- These goals can serve a guide to help us focus on global issues related to ethics and to better align diversity, inclusion and well-being.

How does ethics help us align the ideas of diversity, inclusion and well-being?

At Mason we strive to be a “well-being university”. We also have affirmed that “diversity is our strength.” Our approaches to diversity, inclusion and well-being may be different at times, but there are certainly shared goals. Both are ultimately about helping us to learn the best ways to lead our lives, how to help people reach their full potential and how to make positive changes in society. We need to continue to find good ways to link these two very important and complex topics and the field of ethics is a great way to help align diversity, inclusion and well-being.

- There are many times when we know good ways to contribute to our own well-being and the well-being of others. For example, eating a balanced diet, including locally grown fresh fruits & vegetables. This is good for our own health and energy, can help prevent illness for ourselves and our community, and can reduce our carbon footprint and preserve the environment for others.

- However, what happens when we are not so sure what will best contribute to our own well-being and the well-being of others? What happens when the well-being of one person will infringe upon the well-being of another person?

- You feel that you need to get another degree to help with your career (e.g. career/financial well-being), but are concerned that it will take you away from time with your family (e.g. social/emotional well-being). How do you decide what’s best for your well-being as well as the well-being of your family? What about the well-being of those beyond ourselves and our families?

- You take some time away from your job to recharge, reflect and focus on your personal well-being, but that means that someone who often has less power and privilege, and who is already feeling overwhelmed, has to take on extra work. Whose well-being should be prioritized?

- What if we have others depending on us? Should we sacrifice some of our own well-being for them.

- Research has shown that parents experience reduced subjective well-being when they have children. How much should that influence their decision to have children?

- What about those in the military? Should they sacrifice their own well-being (maybe even their lives) for those they may not even know?

- What happens when we do not focus on the well-being of others? Some people believe that since they themselves are not racist, they can therefore rest peacefully knowing that they are not a perpetrator. They may believe: “I am not a racist, so I am all good”. However, as Professor Marlon James mentions in the video below, having a clear conscience about our own levels of racism will not stop racists. Others may think: “I am not a rapist, so I am all good”. Having a clear conscience about not raping anyone will not stop rapists. If we are not helping to fight injustice we are not doing enough for the well-being of the community, regardless of our personal sense of well-being. Understanding this concept can help us to get beyond focusing only on our own well-being and considering the well-being of all. Integrating some of the principles of ethics can help us here (e.g. Character focus: “What kind of person should I be? (e.g. compassionate, fair/just, respectful, responsible)”; Consequences focus: “What will bring the best results and least harm for all who might be affected?”; Care focus: “How can I treat others as I/they would like to be treated?”). As Professor Marlon James asks in the following video, “Are you non- or anti-?” (see: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/video/2016/jan/13/marlon-james-are-you-racist-video).

- When there is a well-being conflict, should we advocate for whatever benefits the most people: “greatest good for the greatest number” (e.g. Consequences focus)? What about protecting the rights of smaller groups that may be harmed by a “greatest good for the greatest number” focus (e.g. Code focus)?

- In student affairs work, there are often long hours- if this is hurting our own well-being should we do it? What if we are convinced that it is necessary to help the well-being of others (e.g. suicidal students)?

- Consider the immigration debate. Once we have the privilege of citizenship in this country what should we do about others who want to enter? Should we show compassion to refugees and asylum seekers and allow them to enter? Should we keep the borders open and let in every single person who wants to enter? Is there a way to find a middle ground? What is our responsibility to others, beyond our own self-care?

- In order to address these types of challenges, it is essential to have a set of ethical priorities to guide our decisions. Ethics provides us with the time-tested principles that can guide us. These principles often do not provide easy answers, but rather a way to think critically about how we can arrive at an answer. Ethics provides a framework to help balance competing conceptions of well-being through a “checks and balances” approach. A clear focus on ethics can help us to ensure that our well-being initiatives are inclusive and addressing multiple layers (e.g. individual responsibility, situational factors, root causes, organizations/systems, impact on others, etc.). For more about LEAD’s Take 5 approach to ethics, see take5.gmu.edu.

SOURCES

- Association of American Colleges and Universities (2013). It Takes More than a Major: Employer Priorities for College Learning and Student Success. Hart Research Associates, on behalf of: The Association of American Colleges and Universities.

- Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2009). Ethical Reasoning VALUE Rubric. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/ethical-reasoning-value-rubric

- Busteed, Brandon (2014). The Biggest Blown Opportunity in Higher Ed History. Inside Higher Education

- Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (2012). CAS professional standards for higher education (9th ed.). Washington, DC.

- Ciulla, J. (2003). The ethics of leadership. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

- Dugan, J. P., Kodama, C., Correia, B., & Associates. (2013). Multi-Institutional Study of Leadership insight report: Leadership program delivery. College Park, MD: National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs.

Illinois Leadership Center (2013) Leadership Benchmarking Study - International Leadership Association (ILA) Guiding Questions: Guidelines for Leadership Education Programs; http://www.ila-net.org/Communities/LC/GuidingQuestionsFinal.pdf

- Komives, S. R., Longerbeam, S. D., Mainella, F., Osteen, L., Owen, J. E., & Wagner, W. (2009). Leadership Identity Development. Journal of Leadership Education, 8(1), 11-47.

- Komives, S.R., Lucas, N., & McMahon, T.R. Exploring Leadership: For College Students Who Want to Make a Difference (2007). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- MasonLeads leadership assumptions were adapted from Komives, S.R., Lucas, N., & McMahon, T.R. in Exploring Leadership: For College Students Who Want to Make a Difference (2007). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Owen, J. E. (2012). Findings from the Multi-Institutional Study of Leadership Institutional Survey: A National Report. College Park, MD: National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs.

- Prentice, R. (2014). Teaching Behavioral Ethics. Journal of Legal Studies Education, 31(2), 325-365.

- Prentice, R. (2015). Behavioral Ethics: Can It Help Lawyers (and Others) Be Their Best Selves? Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics and Public Policy, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2424249

- Price, T. (2008). Leadership ethics: An introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Wielkiewicz, R. M. (2000). The Leadership Attitudes and Beliefs Scale: An instrument for evaluating college students’ thinking about leadership and organizations. Journal of College Student Development, 41, 335-347.